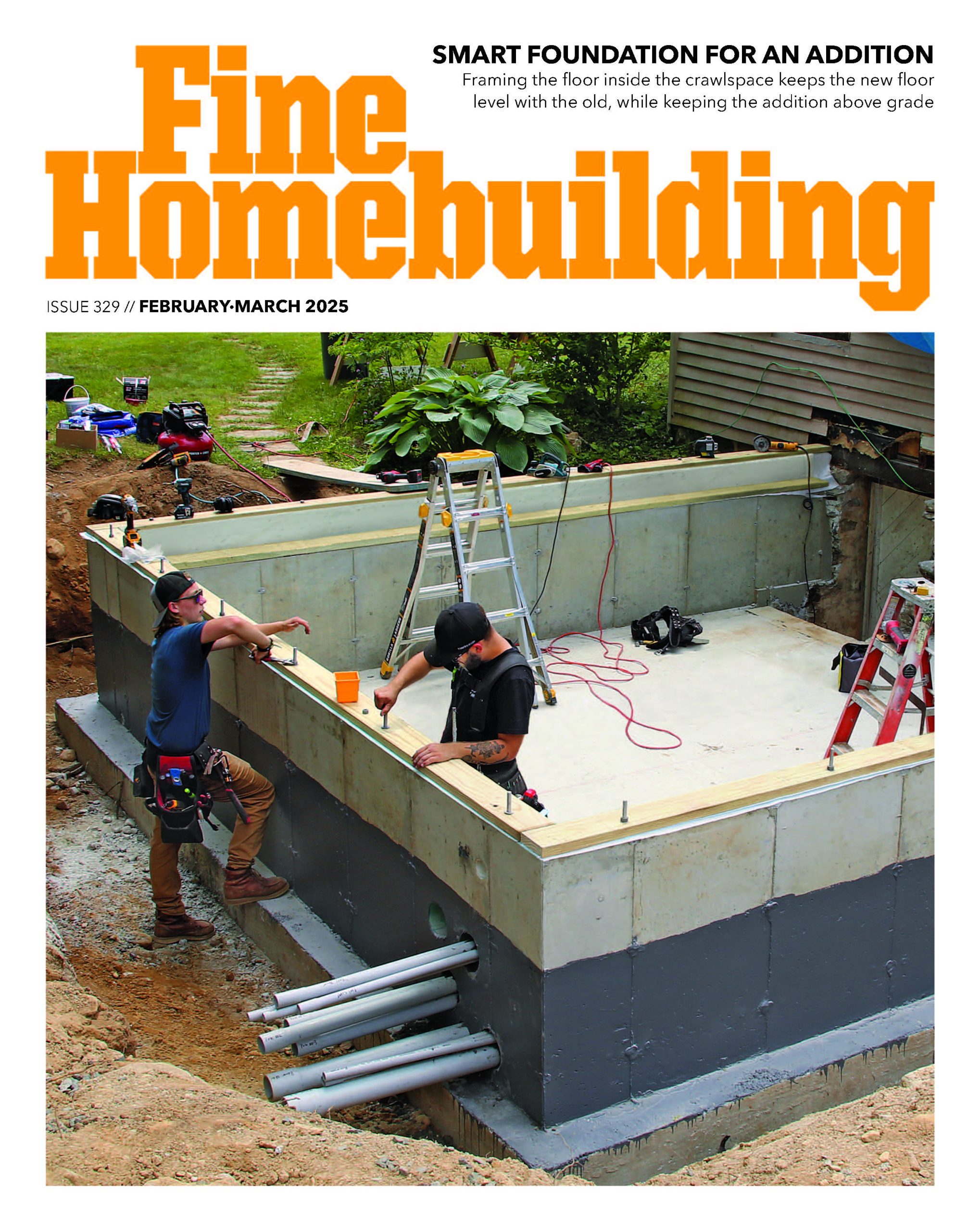

Resurrecting Linseed Oil Paint

This centuries-old paint offers vapor-permeabiity, maintainability, and longevity with zero VOCs, but know its limitations before you get to work.

Modern paints have some benefits, such as fast dry times and flexibility, but they also have some downsides—alkyd paints include nasty solvents, while acrylic paints trap moisture under the surface, causing paint to flake or fail. Linseed oil paint is a plant-based paint first used centuries ago; with the introduction of mildewcides to prevent rot, a linseed-oil-painted surface is easily maintainable and will never loosen or peel.

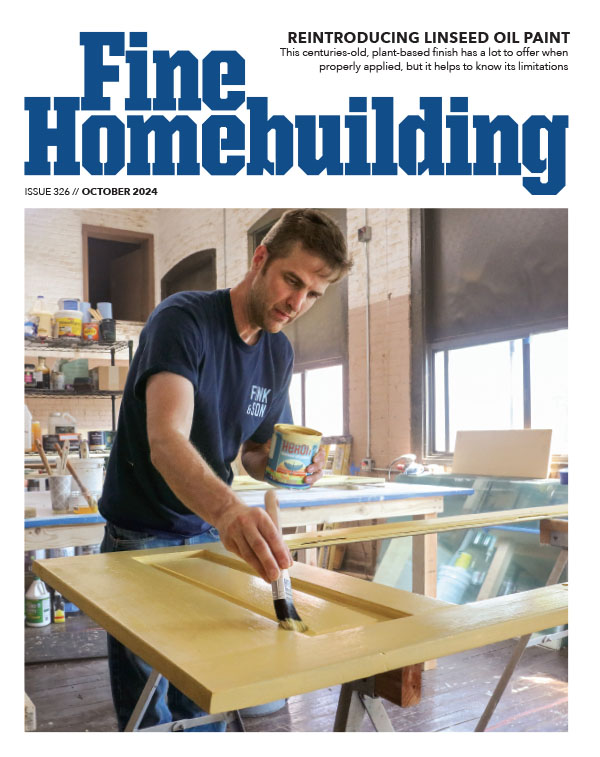

Historical restoration specialist Justin Fink walks through the process of painting a window sash with linseed oil paint, from gathering tools, to the first coat of paint thinned with oil and turpentine, to the final coat and dry-brushing. Options for sourcing linseed oil paint are also included in the article.

Modern Paint Mishaps

My company’s work is focused on restoring or recreating historical exterior elements—windows, doors, and millwork—on houses between 80 and 250-plus years old. The houses we work on have some of the best old-growth lumber that this planet has ever produced, but after a century or more of service, the wood is beginning to fall apart.

So, what’s causing the problems? There is a growing consensus among preservation professionals that our modern paints are to blame. For all the benefits of alkyd and acrylic exterior paints—and there are many, including affordability, flexibility, fast dry times, mildewcides, and more—there are some problems that nobody seems to be talking about.

Mode of Failure

The penetrating nature of exterior oil-based paints makes them a popular choice, especially as a primer coat, but from an environmental and health perspective they have become a disaster. Nearly all modern oil-based paints have no oil in them at all; they are now called “alkyds,” which is another name for synthetic resin.

Even if you’re willing to tolerate the nasty solvents, noxious fumes, and long list of petroleum-based chemical ingredients, you still may not be able to find a can. Alkyds have been banned in at least half a dozen states and restricted to quart-size cans in many others. It may take some time, but it sure seems like the writing is on the wall: Alkyds are not long for the U.S. market.

The strategy for success with modern exterior acrylic paints—which are, for all intents and purposes, plastic—is to encapsulate the surface of the wood. But even if it starts out as a perfect paint job, time always takes a toll.

When water eventually finds its way behind the paint it becomes trapped under the plastic coating, and this encapsulation strategy becomes the mode of failure. Whether the wood rots, the paint flakes, or it manages to hang on long enough that it just wears out from UV damage, the story always ends the same way: scrape, sand, and start again.

So when one of our clients specified traditional linseed oil paint for their project, suggesting it would solve some of our issues—trapped water and maintainability—without the dreaded fumes, I was happy to try it. Four years later, linseed paint has become our go-to primer and paint, and we have used it on dozens of projects, new and old.

I think this centuries-old paint has the potential to overcome the downsides of alkyds and solve a lot of the problems caused by plastic paints, including the tendency toward rot. But linseed paint faces some significant hurdles in today’s market, and its application comes with a learning curve.

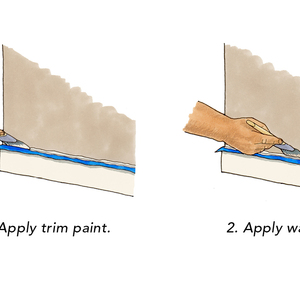

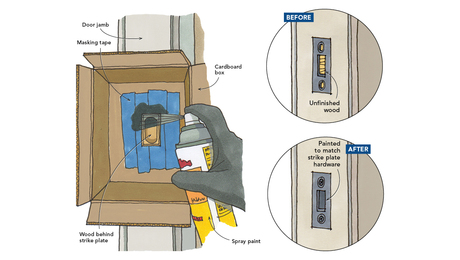

From the Field: Painting Window Sash With Linseed Oil PaintLinseed oil paint is a three-coat system, but you don’t need a separate can of primer—the first coat is just linseed oil paint thinned before application. The biggest mistake most people make it applying it too thick. Very thin coats are key. This paint will stick to just about anything, but you won’t get the full benefits without removing existing paint and getting back to bare wood. Brushes don’t need to be cleaned between coats—just store them in raw linseed oil—but be careful of oily rags, which pose a very real risk of fire. Lay them flat to dry, or soak them in water before disposal. The First Coat Soaks Into the Wood

A Second Coat Adds Coverage

More Coats Even Out Blotching

|

How We Got Here

The use of linseed oil as the base material for paint dates back to the 12th century for artworks and for architectural applications in Ancient Rome. Formulations were simple: linseed oil—made by crushing flax seeds—ground together with natural earth pigments. The slow-drying oil allowed it to seep into the surface of wood, and the pigments provided UV protection and color.

As technology improved, formulations began to include a variety of additives that delivered quicker dry times, better workability, increased mold resistance, and harder finished surfaces. Over time, the amount of linseed oil in the paint decreased and the amount of petroleum-based solvents increased.

By the 1930s, true oil-based paints were being replaced with the synthetic alkyd paints used today. Then, during the building boom that followed World War II, production building and the DIY movement took hold. Fast dry times and ease of use became paramount, and a large store of petroleum by-products from the war effort led to the rise of a new category of paint that improved on alkyds’ flaws.

Latex paint, which would later become known as acrylic paint (today’s versions have little to no latex), was popular immediately. It was easy to work with, had no strong odor, dried quickly, cleaned up with soap and water, and provided some flexibility compared to the harder-drying oil paints.

So in short order, oil paints became alkyds, alkyds gave way to acrylics, and linseed was all but extinct. As Erin Gibbs and Katherine Wonson summarize in their National Park Service technical bulletin, “Purified Linseed Oil: Considerations for Use on Historic Wood,” the change was dramatic: “The rapidity and completeness with which synthetic paints overtook the market is exceptional. Consider that in the span of 60 years, linseed-oil paint, the dominant paint in the U.S. for 200 years, has almost completely faded from consumer consciousness.”

But along with the new paint came new problems, particularly rotting wood and peeling finishes.

Protection Beyond the Surface

Aside from ease of use, perhaps the biggest benefit to plastic paint is that it’s stretchy, which is crucial for a product designed to protect wooden surfaces by completely encapsulating them. Wood moves—seasonally, or in conjunction with structural shifting and settling—so a coating that can take some movement has a fighting chance of hanging on. But if the coating only protects the surface, then when a little water seeps into a crack, or enters the wood from the back side, it can take a long time to dry out, if it does at all.

Gibbs and Wonson explain: “Waterborne coating systems … do little to protect the underlying wood structure, which remains hygroscopic and unprotected. Thus, any water entering a latex-paint system is free to absorb via capillary action into the wood structure.”

Unlike modern paints, traditional linseed paint penetrates the surface of the wood. Heron Paint owner Travis Joslyn explains, “Linseed oil has a lower surface tension than water, so it’s absorbed into these surfaces deeper than water can reach. ”

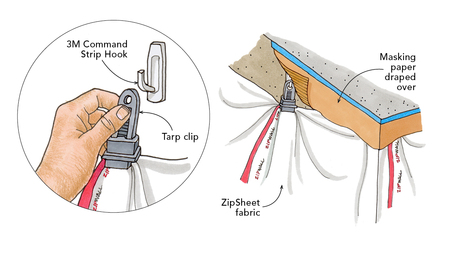

Linseed Paint Starter KitThe tools and supplies needed to work with linseed paint aren’t exotic, but online specialty suppliers are the best option for one-stop shopping. |

Paint Science

The base of linseed paint is boiled linseed oil, which is a bit thicker than raw linseed oil, and combines better with the pigments used to add durability and color. But the thinner and slower-drying raw linseed oil has a lower surface tension than boiled linseed oil or water, making it ideal for thinning the initial coat of linseed paint.

Linseed oil is naturally hydrophobic, which means it repels water. But since the oil doesn’t form a watertight surface layer like acrylic paints, any water that does seep into the wood is able to dry again by wicking to the surface.

As Michiel Brouns, owner of Brouns & Co. and author of Linseed Paint and Oil, explains, “Linseed paint keeps water out for the [most] part, but it also lets any moisture that does get in evaporate out through the paint. This means that water never gets stuck under linseed paint, that timber never gets saturated from the inside, and that any water escaping won’t take flakes of paint with it.”

Although this ability to dry to the exterior is often referred to as the paint being “breathable,” that’s really not an accurate description, since breathability implies that water can move in both directions. Swedish paint maker Ottoson’s literature sums it up nicely: “Linseed oil paint … is moisture-permeable but at the same time waterproof, like a kind of GoreTex.”

These days, if builders are going to use solid wood with a painted finish, they often opt for naturally rot-resistant woods (such as mahogany) or chemically altered woods (such as Accoya), but the penetrating nature of linseed oil reopens the door to wood species that the industry usually dismisses as “too prone to rot,” like Eastern white pine and Douglas fir. In fact, linseed paint adheres to most materials, including wood, metal (where it is a terrific rust-preventative coating), plaster, glass, and even plastic.

Environmental Profile

For paint to be labeled “zero VOC” it has to have less than 5 grams per liter (g/L) of volatile organic compounds. As a point of comparison, the maximum number of VOCs in Heron linseed oil paint is 1.89 g/L. Often the biggest contributor to VOCs in linseed paint is the manganese driers added to speed up the drying process. These ingredients aren’t necessarily going to be found on the paint’s SDS (safety data sheet) either.

“By law, manufacturers do not need to disclose all ingredients, even carcinogens, if they fall below the ‘cut-off values/concentration limits,’” Joslyn explains. “For example, none of the ingredients in our added manganese drier are in quantities above 0.1% (cut-off for disclosure), but we voluntarily list it on our SDS anyway.”

In general, people associate alkyd paints with high VOCs and acrylic paints with low VOCs, but according to Brouns, that’s not always an indication of a healthier product: “The reduction of the VOCs in these paints means they have to add all kinds of other chemicals—stabilizers, chemical emulsifiers, anti-coagulants, phthalates—to make their products work. These paints are no healthier than previous generations.”

It’s also difficult to ignore the environmental concerns of all this failing modern paint. Swiss-based Environmental Action found that 58% of all microplastics in the ocean are from paint, making it the largest single source of microplastic pollution. It’s hard to balance that against faster dry times and easy cleanup.

Sourcing Linseed Oil PaintAs linseed paint gains popularity in the U.S., the number of available options is growing, but sourcing is very skewed toward internet retailers over brick-and-mortar paint stores. Some brands offer a wide variety of colors; others offer a more limited selection and provide guidance on combining them to yield custom colors. The price per can may be a shock, but keep in mind that the contents aren’t an apples–to-apples comparison to alkyd or acrylic paints due to the amount of solids in the can. Linseed oil paint, depending on the color, can cover twice as many square feet as conventional paint. So when compared to the coverage of alkyd or acrylic paint, linseed paint is cost competitive—and may even come at a savings.

|

The Mold Concern

Probably the biggest hurdle for the reintroduction of linseed oil paints is the worry about mold. For many builders and painters, their only experience is with cans of “boiled linseed oil” sold in local hardware stores and paint shops. It soon became common lore that these products, when applied to wood in exterior situations, would bloom with black spots of mold.

The unfortunate truth is that mass-produced cans of oil tend to play fast and loose with their labels. Most commodity-brand boiled linseed oil is not truly boiled at all. The oil is extracted with the help of chemicals, not purified to remove the proteins and mucilage that are highly susceptible to mold growth, and mixed with a variety of heavy metals to enhance drying time.

The next nail in the coffin was in 2007, when Swedish-made Allbäck linseed paint became available in the U.S. through some specialty retailers. Shortly after this reintroduction of linseed paint to America, users reported black spots appearing on their freshly painted projects. It came to light that Allbäck offers zinc oxide—a common pigment that helps fight mold growth—as an aftermarket additive, but not as part of their standard mixing process.

Critics might argue that without white lead, a common and highly effective mold-resistant additive used in paint up until it was banned in 1978, modern versions of linseed paint are too risky. It’s true that zinc oxide isn’t a guaranteed cure-all. “While zinc oxide assists in retarding [mold] growth,” Gibbs and Wonson explain, “it may not be sufficient in climates where wet paint is subjected to these conditions over long periods of time.”

But many linseed paint advocates are quick to argue that any paint, linseed, acrylic, or otherwise, will be at risk for mold growth if there is likely to be very low drying potential or even standing water.

The type and quality of oil used to make the paint, or to thin it for application, matter a great deal as well. “Studies have shown that mold and mildew will happily set up shop on wet, uncured raw linseed oil,” explains Joslyn, “but those same studies have tried cultivating mold on a cured surface, and the mold does not propagate.” This is one of the reasons that linseed paint is made with boiled linseed oil as opposed to raw linseed oil (used only on the first coat); the latter takes a very long time to dry.

So choose a product with thoroughly purified and degummed oil in it, add only raw linseed oil to the primer coat (mixing it separately from the remainder of your paint), and remember that products with small amounts of driers, as well as natural pigments that prevent mold growth, are a good thing.

Maintenance Is Needed and Doable

The hard truth is that there’s no such thing as a maintenance-free finish. The typical life expectancy of premium exterior acrylic paint is five to seven years, maybe 10 if you’re lucky. In the case of acrylic paints, “maintenance” means adding another coat of paint, which reduces vapor permeability and increases the chance of rot and paint failure. The cycle continues until there is no choice but to scrape or strip off all the layers of paint and start over.

Unlike with alkyd or acrylic paints, a linseed-oil-painted surface is truly maintainable. As the oils in the paint dry over the years, the pigment will take on a matte, sometimes chalky appearance, signaling it’s time for maintenance. Typically, this happens after about five years, possibly less, depending on exposure and conditions.

It’s worth noting that the maintenance at this point is mostly cosmetic, because even when linseed paint starts to go matte, the wood is still protected by the oil in its pores. At this point, the original linseed paint can be renewed by wiping or brushing a thin coat of boiled linseed oil onto the surface.

Although not typically necessary, you could also add a fresh coat of linseed paint. One exception is noted in the Linolie & Pigment brand linseed paint literature. It reads: “White [linseed paint is] usually not oiled, but painted more often, as the color may become smokier because the oil is yellow.”

Whether maintaining by adding a coat of oil or a fresh coat of paint, here’s the best part: At no point in the life of linseed paint will the surface loosen or peel. And you’ll never have to scrape it off to start again.

Change Is Uncomfortable

I don’t think linseed paint will be right for everybody. It demands a conversation with clients to see if it’s a good fit for the project, and sometimes it just isn’t. At this point in time, it’s not an off-the-shelf purchase in most areas of the country, it has a limited color palette compared to the countless options from acrylic paint companies, and there are limited options for a finished sheen that will all fade to matte over the years.

For professional painters, it will be an unknown product that requires a change in application techniques. Because linseed paint seeps into wood more than acrylic paint, it can’t be relied on to fill and hide surface imperfections. It can’t be easily sprayed, if at all; it has a slow dry time; and there is a more frequent maintenance cycle. In short, expectations will need to be set.

But for anybody willing to make those sacrifices, the reward is the peace of mind that comes with a zero-VOC formulation that won’t be an environmental hazard. You will have painted surfaces with a deep, penetrating level of protection that are maintainable and will never peel, chip, or need to be scraped away to start over. To me, the pros more than outweigh the cons.

— Justin Fink; owner of Fink & Son Historic Restoration in Connecticut. Photos by Brian Pontolilo and Rodney Diaz.

RELATED STORIES